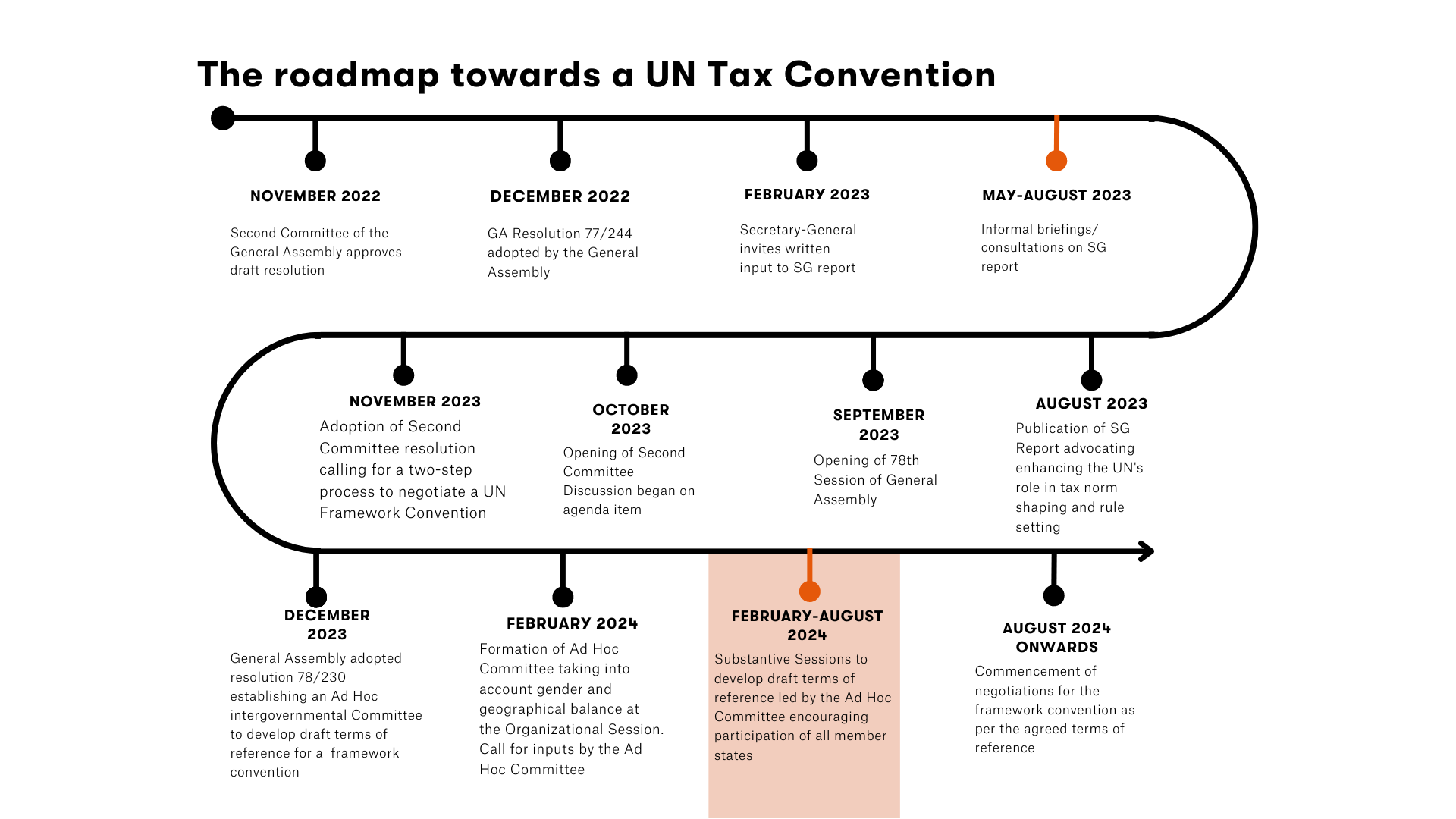

We are fast approaching the first substantial negotiations for the United Nations Framework Convention on International Tax Cooperation (UNTC). The upcoming round will lay the foundation for the content and, more importantly, the aims and objectives of this historic convention. Before the Ad-Hoc Committee meetings start this week, we analyze the key demands and issues that member states and other relevant stakeholders are putting on the table.

By Pulkit Palak, International Law & Human Rights Fellow at CESR

In December last year, countries from the Global South, led by the Africa Group, achieved significant success at the United Nations when a landslide majority passed a resolution favoring a UN framework convention on taxation. Preliminary negotiations on its terms of reference took place in February, and stakeholders (including member states and civil society organizations) have actively contributed their inputs. CESR’s submission emphasized the importance of adopting international human rights law as part of the guiding principles of the convention, which was endorsed by 30 organizations from around the world, including ActionAid, Amnesty International, Oxfam, Save the Children, and Tax Justice Network, among others. Despite initial resistance from powerful stakeholders, the establishment of a diverse and representative bureau and agreement on decision-making procedures signal a participatory approach to reform.

As the process unfolds, closely examining these inputs will be crucial in shaping the direction of global tax reform and ensuring that it is inclusive and effective in addressing pressing economic and social challenges.

The call received 103 inputs in total, including 49 responses from United Nations Member States. These numbers indicate strong engagement with the international tax debate now that the UNTC is a certainty. A similar call for inputs from the Secretary General last year received 92 submissions in total, which consisted of only 28 responses from Member States (read our analysis here). Hence, the engagement of Member States has considerably increased. Other inputs include 1 from a member of the UN Committee of Experts on International Cooperation in Tax Matters, 4 from United Nations Organizations, 6 from other international organizations, 10 from businesses and others, and the remaining 33 from civil society and academia.

Inputs submitted by the Member States

While in earlier stages we saw a major drift between the blocs supporting and opposing the need for a United Nations-led convention on international tax, the debate has now shifted to substantive and procedural issues. On a positive note, due credit must be given to the increasing understanding within member states of the relationship of international tax with different cross-cutting fields of climate mitigation and adaptation, and sustainable development goals. Out of the 49 member state responses, 36 referred to the importance of an efficient international tax system to support the achievement of developmental goals through resource mobilization and/or other means. Consequently, we also noted increased emphasis from the member states on the intersection of international taxation and the environment, where 13 inputs discussed the inclusion of environmental taxation and ideas such as carbon pricing, carbon credits, and trading. In fact, green transition and environmental taxation were a major portion of France’s brief submission to the Ad-hoc Committee.

On the procedural front, most member states agree on the basic structure of the instrument: that the framework should make way for a Conference of Parties (CoP), as the main decision-making body, with a secretariat separately formed to aid the CoP in addition to establishment of subsidiary or advisory bodies to provide technical support. Several inputs -including the Africa Group’s submissions- highlight the existing UN Committee of Experts on International Cooperation in Tax Matters and suggest that their role should be reconvened as an advisory body to the framework (a possibility also discussed in the preliminary negotiations in February). The preliminary discussions also raised the possibility of simultaneously negotiating early protocols along with the negotiation of the framework convention itself. However, based on the inputs, there seems to be a consensus amongst the member states that the negotiation of protocols should be carried out second to the finalization of the Framework Convention, and not through the ad-hoc committee, given the intricacies and technical expertise required.

In answering the poignant question of specific problems that the framework convention could address, there was increased emphasis on taxation of cross-border services, digital taxation in particular, and corporate taxation rates/harmful tax competition. It must be noted here that both these problems are currently being targeted by the OECD’s Two-Pillar Solution. However, these OECD reforms also recently prompted intervention from various UN experts who warned that the reforms could widen inequality within and between states. As OECD continues its push for adopting a multilateral agreement on cross-border taxation, these issues and their proposed reforms will be part of the terms of reference negotiation discussions.

Other popular substantive issues included the curbing of illicit financial flows, taxation of high-net-worth individuals, and fair distribution of taxing rights. Low and middle-income countries especially advocated for the latter two. Amongst other international tax issues, the role of wealth taxes in promoting equality and financing the SDGs (which was recently discussed in the 2024 Economic and Social Council Special Meeting on International Cooperation in Tax Matters this March) was also a critical component of some member state inputs. Surprisingly, wealth taxation was not brought up by Brazil in their input (even though they are campaigning for the same in the G20 discussions!).

Following suit from last year's submissions, the Africa Group submitted a consolidated response on behalf of 54 African Union Member States. Amongst other responses, there are also individual inputs from 5 Latin American (Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru), 2 Caribbean (Jamaica and Bahamas), and 2 South Asian countries (India and Pakistan). Wide participation from the Global South during this process is a positive step forward toward the decolonization of international tax debates. On the other hand, there was no coordinated response from the European Union this time, even though 18 out of 27 European Union members took the time to send in their individual responses.

Inputs from countries like Belgium, Czechia, Estonia, Ireland, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Slovenia, and Sweden, amongst others, pressed mainly on two points. First, that the work of the framework convention should build on existing arrangements (referring to the OECD-led status quo). Second, that decision-making should be consensus-based. These points were also raised by their allies, including Japan, Singapore, Israel, and Saudi Arabia. In a similar fashion, the OECD also did not submit a coordinated response, unlike last year; however, 31 out of 38 of the OECD members submitted individual inputs. Regarding the OECD’s reiterated concerns about duplication, the Africa Group and other lower-income countries addressed these and other recurrent critiques under the terms of legacy issues—to acknowledge and build upon existing arrangements in order to avoid over-complication in tax governance. The pushback by the Global North, on the other hand, was a natural extension of their previous arguments claiming efficiency and tax certainty of the existing OECD regime.

The argument for consensus-based decision-making remains an outstanding source of tension. Although partially settled during the preliminary negotiations through mutually agreed language, the intention of the negotiations will be to strive for consensus, failing which UN general assembly voting rules (simple majority) will apply. However, supporters of the OECD regime insisted in their inputs that decision-making under the convention should be consensus-based. 24 of the member state responses, i.e. exactly half, came out to support consensus-based decision-making. To better understand the issues surrounding simple majority versus consensus-based, we go back to the powerful statement of the representative of Bolivia at the February preliminary negotiations of the Ad-hoc Committee: “Best demonstration for our quest for consensus is the very existence of this committee. We are absolutely interested in working towards consensus but saying that consensus is a requirement to the work is giving veto power to delegations when it comes to this process, and this is very dangerous. There is a common interest to achieve the greatest degree of consensus but that can't mean that we let our work reach an impasse.”

Other inputs

Apart from the inputs provided by sovereign member states recognized by the United Nations, 3 self-governing British Crown Dependencies: Isle of Man, Government of Guernsey and Bailiwick of Jersey (famous for enabling tax abuse) took the opportunity to submit inputs as other stakeholders. The self-governing jurisdictions advocated for the representation of autonomous tax jurisdictions in the spirit of making the framework convention truly inclusive. Other business stakeholders, such as KPMG, the Information Technology Industry Council (ITI), and the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC), discussed the importance of avoiding duplication and a consensus-based approach following the OECD bloc.

Lastly, the submissions made by United Nations Entities, international organizations, civil Service, and academia remain consistent with the submissions of the member states. They include automatic information exchange, beneficial ownership registration, progressive taxation of personal wealth, tax sovereignty, transparency, equity, and climate justice, amongst others. These submissions are vital for one reason: they link the cross-cutting impacts of taxation on inequality, climate justice, development, gender equality, and human rights. Over and above the increased recognition of a sustainable development perspective from the member states, the response from civil society and other organizations actually explores into the interconnectedness of these realms.

The joint civil society and trade unions submission from the Civil Society Financing for Development Mechanism alone had a whopping 144 signatories, discussing the links between tax and gender equality and taxes and human rights. In addition to our own submission, we also helped coordinate a joint civil society submission on the importance of tax and gender equality on behalf of gender and tax advocates and another submission on tax and climate financing with 4 organizations endorsing it. International recognition and calls for the inclusion of human rights principles in global tax debates have never been more extensive and active. The inputs from civil society have also been critical, campaigning for equal treatment for and effective participation of developing nations. Suggestions include the importance of aid for funds that will enable developing nations to contribute constructively, as well as conducting hybrid consultations and live streaming for transparency.

Conclusion

The wide range of submissions exhibits the larger willingness in developing nations and civil society to accept the multifaceted role of taxes to generate revenue, redistribute, re-price, provide representation and reparation, and the insistence to embrace them in the international taxation norms. However, the same is not reflected in the first draft detailed agenda for the UN Tax Convention Committee's First Substantial Session. Despite the standup acknowledgment from the member states regarding the importance of a sustainable development perspective or civil society concerns regarding tax and cross-cutting issues of gender and human rights, discussions of these issues are not on the agenda so far.

As we approach the negotiations for the Framework Convention, it becomes imperative to remember what the opportunity truly represents: “a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to fix discriminatory and regressive international tax rules,” a chance to embrace the corrective powers offered by taxation and to prepare a framework based on just and fair principles of human rights, capable of withstanding future shocks and developments instead of one merely satiating current problems. All relevant stakeholders must continue engaging in the same collaborative spirit that was exhibited in the preliminary negotiations as we approach the important stage of negotiation of the terms of reference, which will ultimately determine what the framework convention and the new global tax architecture will look like.