Francesco, a 60-year-old engineer from northern Italy, lost his job as a result of the global financial crisis in 2008. Newly unemployed but with a modest income during the previous year, Francesco found himself in a bind. Francesco’s income history precluded him from receiving free health services, but he also could not afford the €750 fee required for much-needed dental care. With an unsightly smile Francesco’s chance at succeeding in job interviews were slim, and he was still too young to be eligible for a pension.

Francesco, a 60-year-old engineer from northern Italy, lost his job as a result of the global financial crisis in 2008. Newly unemployed but with a modest income during the previous year, Francesco found himself in a bind. Francesco’s income history precluded him from receiving free health services, but he also could not afford the €750 fee required for much-needed dental care. With an unsightly smile Francesco’s chance at succeeding in job interviews were slim, and he was still too young to be eligible for a pension.

Stories like Francesco’s are now very common in Italy and they shed light on the human effects of the Lost Decade since the global economic crisis began in 2008. According to a recent report, in 2015, 12.2 million, or 1 in 5 Italians, went without medical care and 7.8 million spent all their savings on healthcare, contracted a medical debt, or both. As revealed by Eurostat, unmet needs for dental care are particularly high: 13.7% of the Italians in the poorest quintile could not afford dental care in 2008, and this reached 19.1% in 2015 and remained high, at 16.9%, in 2016.

Italian austerity measures threaten health care accessibility

Unaffordable medical care is in fact a new phenomenon in Italy, a country whose public healthcare system is based on the principles of universal coverage and protection from financial hardship. The Italian National Health Service (SSN – Servizio Sanitario Nazionale) provides automatic coverage to all citizens, legal foreign residents and migrants holding a residence permit. In 2000, the WHO ranked Italy’s health system as the second best in the world, after France.

What explains the Italian health system’s recent fall from grace? Increasingly, draconian austerity measures are undermining Italians’ right to health. Soon after the Eurozone sovereign debt crisis, Italian health spending relinquished its ten-year positive trend and began a gradual, yet consistent, decline. In 2012, the Italian government passed a series of decree laws reducing total public health financing by €900 million in 2012, €1.8 billion in 2013 and a further €2 billion in 2014, decreasing resources for essential medicines and the National Health Fund. Moreover, between 2009 and 2010, SSN personnel were reduced.

The decrease in central funding necessitated increased co-payments and cost-saving measures to reduce pharmaceutical spending. Co-payments for outpatient drugs and specialized procedures and visits have also increased by an astounding 53.7% over the 2007-15 period. Healthcare accessibility—a key factor in the right to health—has suffered grievous injuries due to such harsh austerity cuts.

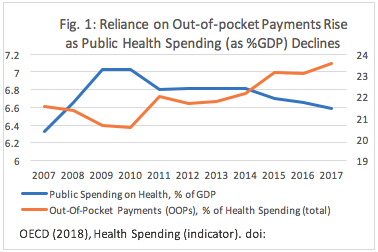

After the implementation of the first round of austerity measures in 2010, the out-of-pocket payments (OOPs) families had to make as a percentage of total health spending began rising sharply, concurrent with a decrease in the government’s health spending. After eight years of fiscal contraction, the percentage of OOPs reached almost a quarter of the overall expenditure on health. The payments Italians are forced to make for health care are now above the EU average, doubling those of France and resembling those in Greece and Spain—both also austerity-affected countries. This impacts people’s enjoyment of the right to health because high levels of OOPs undermine affordability, constituting a significant barrier to accessing healthcare. Simultaneous with these jumps in healthcare costs, excessive waiting lists have been widely documented throughout the country since 2008-2010. For example, over 33% of all patients waited more than three months for hip replacement in 2017.

After the implementation of the first round of austerity measures in 2010, the out-of-pocket payments (OOPs) families had to make as a percentage of total health spending began rising sharply, concurrent with a decrease in the government’s health spending. After eight years of fiscal contraction, the percentage of OOPs reached almost a quarter of the overall expenditure on health. The payments Italians are forced to make for health care are now above the EU average, doubling those of France and resembling those in Greece and Spain—both also austerity-affected countries. This impacts people’s enjoyment of the right to health because high levels of OOPs undermine affordability, constituting a significant barrier to accessing healthcare. Simultaneous with these jumps in healthcare costs, excessive waiting lists have been widely documented throughout the country since 2008-2010. For example, over 33% of all patients waited more than three months for hip replacement in 2017.

All of these factors illustrate the fact that Italian austerity measures threaten the accessibility dimension of the right to health, a right that Italy recognizes as a signatory to the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), but also with its Constitution. In other words, when the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR) expressed serious concerns about the enjoyment of health in Italy, the claim was fully backed by this hard evidence.

Austerity widens health inequalities

Austerity measures are also driving increased inequalities in health in Italy, as the impacts are unevenly distributed across income groups. Since the start of the crisis, the percentage of the poorest people in Italy suffering from unmet medical needs has been steadily growing—as high as 15.5% in 2015. By contrast, the number of people in the highest income brackets reporting foregone care is below 1% over the period from 2008 to 2016. Perhaps even more astonishing, the percentage of rich Italians reporting unmet medical needs has actually decreased since 2008. Austerity has also widened geographical health inequities, with many districts in the South struggling to meet the minimum levels of assistance guaranteed by law. Clearly, the already most disadvantaged groups are bearing the heaviest burden of contractionary fiscal policies in Italy.

Alternatives to austerity

Is austerity unavoidable in Italy, or are there alternatives? The long-term deleterious effects of contractionary fiscal policies on employment and output, not to mention socioeconomic well-being, have been repeatedly highlighted by heterodox and orthodox economists alike. In Europe, the cases of countries such as Iceland, Poland, Switzerland and Portugal (after 2013) show how economic recovery can be realized in line with international human rights law, without renouncing efficiency and financial viability.

Looking at the Italian economy, alternatives to austerity that would reduce the debt-to-GDP ratio or boost revenues include: financing at least a segment of the sovereign debt through bank loans, instead of financial market lending; combating fiscal evasion which, notwithstanding the efforts of the Italian government, generates losses as high as €75.5 billion in 2014; increasing the progressivity of the Italian taxation system, which would shelter low- and middle-income households from the worst impacts of the crisis, while stimulating aggregate demand in times of financial turmoil.

Sadly, the current Italian government is considering a tax reform which would only further entrench tax injustices. The far right-wing party Lega Nord aims to introduce a radically new fiscal regime based on a flat tax rate of 15% contrasted with current progressive rates of 43% for top income earners and 24% for corporations. Proponents maintain that a single, uniform, low tax rate would decrease the tax burdens citizens face, while simplifying the system to make tax avoidance more difficult, and boosting the economy.

Yet history shows that cutting taxes to grow an economy almost never works, only reducing the fiscal space available to realize socioeconomic rights, further eroding welfare state provisions and actually putting a drag on economic dynamism. Introducing such a regressive system would redistribute wealth upward, overwhelmingly benefitting the richest. In fact, an analysis from the Italian financial newspaper Il Sole 24 Ore has estimated that single-income families (often led by women) would be hit the hardest, while top-earners would gain considerably.

Francesco eventually found a helping hand from the humanitarian agency NGO Emergency, whose clinics offer free health services to migrants and people in need. However, healthcare is not a matter of charity nor is it a commodity. Given all the alternatives available, it is incumbent on the Italian state to assess the human rights impacts of its austerity measures, and use its maximum available resources to ensure the enjoyment of the right to health, maintaining healthcare that is affordable for all and protecting the most disadvantaged groups during troubling economic times.