This week, I joined the one third of the US population to have received at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine. Though I feel very fortunate to have received this first essential protection against the virus, I won’t be posting the compulsory selfie about it on social media, as it’s more a marker of privilege than a motive of pride.

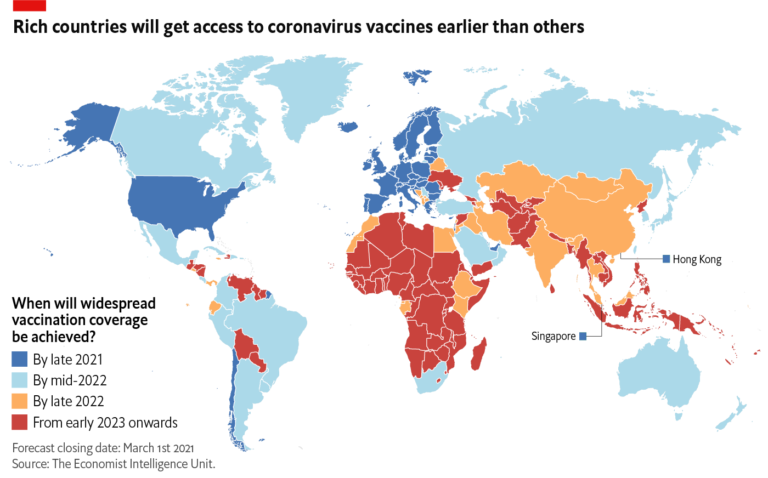

An image the world does need to see is the global selfie below: an updated snapshot of our world’s emerging vaccine apartheid. While those of us in the US and Europe (and a few other largely wealthy countries) can all expect to be vaccinated this year, those in most other countries face waits of up to several years. For most middle-income countries, including India and China, the timelines will likely extend into late 2022. In low-income countries, widespread vaccination coverage will not be achieved before 2023 or even 2024, if it happens at all.

To date, 86% of vaccine shots have been administered in high and upper-middle income countries, with only 0.1% in low income countries. While almost a third of North American adults have now received a first dose, in Central America that figure is 3%, and just 0.4% in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Why these disparities? Because high-income countries are monopolizing vaccine supply and production. Rich countries, with just a fifth of the world’s adult population, have bought up more than half the vaccine doses purchased to date - in some cases, up to five times more than they need to cover their populations. Low and middle-income countries, with four fifths of the global population, have acquired less than a third. The remaining 13% of doses have been bought by COVAX, a WHO-led initiative whose goal of guaranteeing fair and equitable access to vaccines in poorer countries is being undermined by serious shortcomings in scale, autonomy, and transparency.

As well as hoarding the current vaccine supply, the US, UK and EU (and their pharmaceutical companies) are actively and persistently blocking efforts led by India and South Africa at the WTO for a temporary waiver of intellectual property rights until global herd immunity is achieved. This waiver would enable countries in the global South to ramp up vaccine production and manufacture of existing vaccines until the pandemic subsides. Scores of countries in Africa, Asia and Latin America have rallied behind the waiver request. Yet the map of countries obstructing it mirrors the one above. It is beyond ironic that these same blocker countries’ governments (and media) are also accusing countries such as China and Russia of “vaccine diplomacy” for advancing their geopolitical interests by developing and delivering vaccines to countries in Latin America and elsewhere.

There can be no starker illustration of what UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres has decried as the “severe limitations of global cooperation and governance” in response to the pandemic. Exhortations to global solidarity, so liberally proffered in international forums around its one-year anniversary, ring hollow in the face of such dynamics. Several heads of state have recently called for a new international treaty on pandemic preparedness and response. Yet the normative framework for global cooperation to protect everyone’s health, life and livelihood in such contexts already exists. What’s lacking is the political will of governments and corporations to respect it.

The vast majority of the world’s governments have already signed up to binding international standards that establish an obligation to provide international cooperation so that all governments can resource and realize the right to health and other socioeconomic rights for all people, a duty particularly incumbent on states with greater capacity. Complemented by “soft law” principles on access to medicines, corporate accountability and extraterritorial obligations (duties beyond borders), these standards provide a detailed normative basis for compelling states to cooperate through knowledge and technology transfer and other measures to protect public goods over private profit, and to ensure an equal share in the benefits of scientific progress. At minimum, they impose a duty to “do no harm”, including by lifting unfair debt, tax and intellectual property practices that restrict poorer countries’ resources and room for manoeuvre. The SDGs underscore these obligations, affirming the right of developing countries to use trade-related flexibilities to provide access to medicines for all.

Such commitments, however, will remain a dead letter without concerted mobilization by civil society groups, social movements and outraged individuals, fueled by the global solidarity so manifestly lacking between governments. That is why we at CESR have joined the worldwide campaign for a People’s Vaccine, calling for the vaccine to be made available to all as a global public good and for international vaccine cooperation to be seen as a human rights obligation. We’ve also been working with partners such as Treatment Action Group and Partners in Health to frame international cooperation on access to vaccines and global health financing as a human rights imperative. Our broader work in response to the pandemic has also spotlighted the inequalities it has magnified – within and between countries - and the crucial role of rights-centered fiscal responses in addressing these. Our goal has been to highlight how we can invoke government’s human rights obligations in concrete and actionable ways to challenge this disparity and push for accountability.

Wealthy countries and their pharmaceutical companies have shown themselves too selfish and too short-sighted to be politely persuaded to show solidarity with those on the other side of the divide. It’s time to deploy a fuller arsenal of tools to compel them to cooperate as a matter of justice and human rights. And if you are also lucky enough to get vaccinated soon, please add your voice to the demands for everyone to get a fair shot, both locally and globally.