Extreme economic inequality is increasingly recognized as one of the most pervasive threats to human rights of our time. The scale of global inequality is shocking. While the combined wealth of the world’s ten richest billionaires exceeds that of whole nations such as Switzerland, Sweden and Norway, one in ten people worldwide continue to live in extreme poverty on less than $1.90 a day.

Extreme economic inequality is increasingly recognized as one of the most pervasive threats to human rights of our time. The scale of global inequality is shocking. While the combined wealth of the world’s ten richest billionaires exceeds that of whole nations such as Switzerland, Sweden and Norway, one in ten people worldwide continue to live in extreme poverty on less than $1.90 a day.

Even more alarming is the escalation of income and wealth concentration over the last three decades. Since the 1980s, the income of the richest 1% has increased twice as much as those of the poorest 50%. The number of billionaires who own as much wealth as the bottom half of humanity has gone from 380 to 26 over the last decade. This indicates that our economic and political systems are working primarily for the ultra-rich, negating the Universal Declaration of Human Rights’ basic premise that all human beings are “equal in dignity and rights.”

Combating extreme economic inequality has been at the core of CESR’s mission for many years. Our research demonstrates how the rise in extreme inequality is both a cause and consequence of human rights violations. Its implications for the full gamut of human rights have become abundantly clear, as the rising disenchantment with democracy it has bred has fueled populist, authoritarian and ethno-nationalist political forces across the globe. Income and wealth disparities have also been shown to translate directly into starkly unequal economic and social rights outcomes, such as in education, health and life expectancy, and they also entrench gender inequality more deeply.

What is often overlooked is that extreme inequality is the result of deliberate policy choices that breach human rights and have enormous redistributive implications. Those choices include austerity measures that deplete social spending, affecting women and other disadvantaged groups disproportionately; regressive and discriminatory tax policies that effectively concentrate wealth at the top; labor market policies that erode workers’ rights and the power of unions, and rely on women to shoulder the unpaid care burden; weak social protection systems and privatization processes that place private profit over public goods such as health and education.

CESR challenges the abusive policies and practices fueling extreme inequality through a diverse set of advocacy channels. We work with partners in multiple countries to bring evidence of the human rights impacts of inequitable policies before human rights accountability mechanisms, and call for redistributive alternatives. Our aim has been to prompt these bodies to hold states accountable to their obligation to deploy the “maximum available resources” to progressively realize social and economic rights for all, without discrimination or retrogression--a vital but underused principle for tackling economic inequality.

In Spain, for example, we forged a coalition of groups to make the case before the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights that austerity measures implemented in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis were clearly retrogressive and had made Spain one of the most unequal countries in Europe. Following strong Committee recommendations to avoid retrogressive measures, the government in 2018 announced the restoration of universal access to health care, citing its human rights obligations as justification.

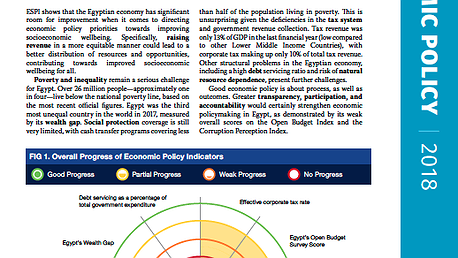

CESR also targets influential economic and development governance institutions whose policy prescriptions directly impact economic inequality. We have challenged the International Monetary Fund (IMF) on its support for austerity measures, drawing on evidence from countries such as Brazil and Egypt that proves these policies have exacerbated economic and gender inequalities. CESR is also using the unprecedented global commitment to reduce systemic inequality within and between countries (Goal 10 of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development) as a spur to action toward meaningfully redistributive socioeconomic policies at the national and international level.

Another systemic obstacle CESR focuses on is transnational tax abuse. Facilitated by some of the world’s richest countries and others acting as tax havens, tax abuse by multinational corporations and wealthy individuals deprives so-called developing countries of resources on such a massive scale that it dwarfs the official development assistance they receive. Our work generates greater human rights accountability for this driver of global inequality in multiple venues. Collaboration with partners in the tax justice movement led the CEDAW Committee to call on leading tax haven Switzerland to periodically assess the extra-territorial impacts of its financial secrecy policies on women’s rights and equality. We have also contributed to the OECD’s corporate tax reform process as a Steering Group member of the Independent Commission on the Reform of Corporate Taxation (ICRICT).

Alongside the research and advocacy CESR does around inequality’s human rights implications, we work to enable an array of partners to address economic inequality on similar terms, promoting understanding and debate around economic inequality as a human rights issue, fostering skills among CSOs, social movement networks and national human rights institutions, and supporting treaty bodies, special rapporteurs and other intergovernmental actors in this work. Over the years we have forged alliances with development NGOs, trade unions, tax justice campaigners and feminist and environmental networks, among other other movements fighting inequality.

Human rights strategies to combat extreme inequality make a difference by framing it as an injustice and providing a universally-agreed normative framework to tackle it. They tie economic inequality directly to other forms of inequality and discrimination that operate in tandem with it. And they open up a complementary infrastructure of accountability to be used by those seeking to challenge a whole range of inequitable policies and practices. CESR’s work has contributed substantially to increased scrutiny by human rights bodies of governments’ choices around economic inequality, as well as to the greater use of human rights arguments and strategies by actors beyond the human rights movement. It has also chipped away at the longstanding resistance of international financial institutions to engaging with human rights in the context of inequality-reduction.

Extreme inequality is on the political agenda across the globe. Given its corrosive impacts on human rights, it must be central to the human rights agenda too. CESR remains committed to developing robust, rights-based responses to disrupt economic inequality and the structural factors fueling it.