The outcome text just approved for the Fourth International Conference on Financing for Development (FfD4) comes at a critical moment for human rights and the economy. What will it take to turn this agreement into meaningful action against the deep inequalities built into global financial systems? Here, we take stock of the history of this UN summit and outline what needs to happen next to ensure it leads to real, lasting change.

By Mahinour El Badrawi, Global Partnerships Lead, Dr. Maria Ron Balsera, Executive Director, and Auska Ovando, Communications Manager, all at CESR.

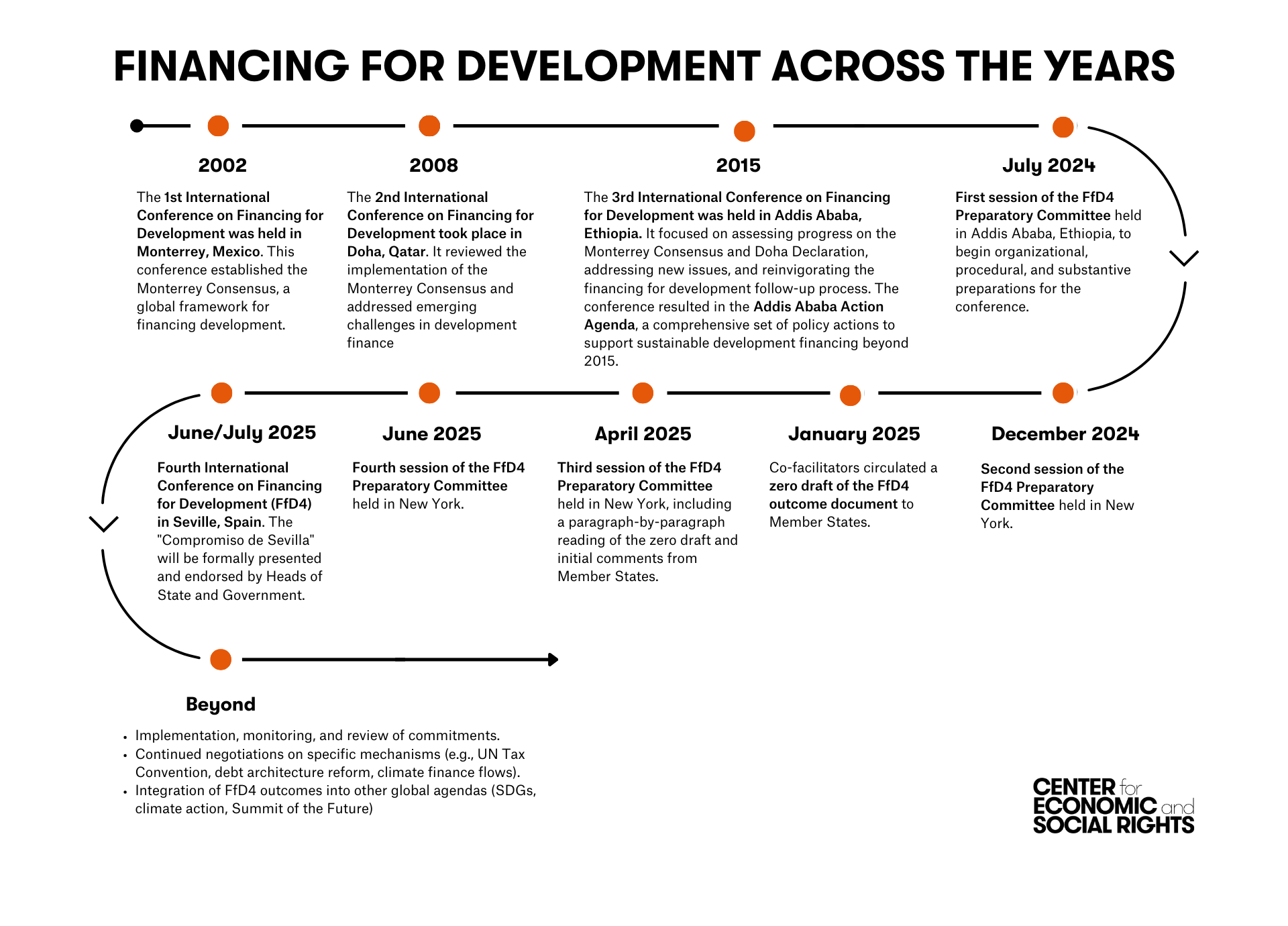

The Financing for Development process, launched in Monterrey in 2002, was meant to reform the international financial system to support equitable and sustainable development. But across follow-up summits in Doha (2008) and Addis Ababa (2015), the core goals of fair taxation, just debt governance, and sufficient public investment have gone unmet.

This failure is not due to lack of alternatives. From the outset, Global South governments and civil society organizations have advanced clear proposals for how to democratize financial governance and fulfill human rights obligations. What has been missing is political will.

For a more detailed history of this process and what brought us to this moment, see our previous blog, All roads lead to Seville.

What the Seville outcome (Compromiso de Sevilla) says—and what it omits

The process leading to the adoption of the outcome text revealed the depth of unresolved political tensions. The final negotiations were marked by the repeated extension of the “silence procedure,” as disagreements remained around debt justice, climate finance, gender equality, and international tax cooperation.

Global North countries (including the United Kingdom, the European Union, Australia, New Zealand, Switzerland, and Japan) blocked key proposals for inclusive UN-led reforms. These included intergovernmental debt negotiations, frameworks for debt cancellation, and the establishment of a permanent forum for international tax cooperation under the UN. Instead, they pushed to keep power within the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and creditor-driven forums.

Civil society organizations also raised concerns about transparency and process—especially around how different proposals were included or excluded. The role of the co-facilitators (Mexico, Norway, Zambia, and Nepal) and co-chairs (Portugal and Burundi) was called into question as efforts to maintain consensus diluted ambition.

Amid this political gridlock, Global South negotiating blocs such as the Africa Group and the Alliance of Small Island States came under pressure to accept weakened language.

Still, the final text (referred to as the Compromiso de Sevilla—which despite closely resembling “compromise” in English, it means “commitment”) may create space for renewed initiatives, including a possible General Assembly resolution on a United Nations Convention on Sovereign Debt. This would follow the example of the Africa Group’s 2022 resolution that launched negotiations for a UN framework convention on international tax cooperation.

Despite the document’s adoption by consensus, the negotiations laid bare deep fractures in the multilateral system. The U.S. not only rejected key elements of the text—on debt, tax, gender, and financial regulation—but fully withdrew from the FfD process, including the Seville conference. Several Global North countries, including the EU, UK, Switzerland, Canada, and Japan, issued dissociations from core provisions, particularly those concerning a sovereign debt workout mechanism and the establishment of a UN tax convention. These positions reflect a broader resistance to shifting financial governance away from creditor-led and OECD-dominated spaces toward more inclusive, rights-aligned institutions under the UN.

Nonetheless, many Global South governments, including the Africa Group, G77+China, and a number of MICs, welcomed the outcome as a cautious but significant step forward. The Compromiso de Sevilla opens pathways for renewed efforts to address structural debt injustice and advance global tax reform, including a first of its kind potential to reaching taxation of high net-worth individuals, through its reference to UNTC, as well as the reference to gender-responsive taxation, both of which would have transformative impact of financing rights-based development. It also opens pathways for the potential for a UN General Assembly resolution on a Sovereign Debt Convention. While the final text is non-binding and weakened by compromise, it represents a political foothold for coalitions pushing for deeper reform.

Civil society allies, including MENAFem and Eurodad, have underscored that this consensus was shaped through political pressure and procedural trade-offs, highlighting the limits of current multilateral dynamics and the urgency of systemic change. These developments reinforce the need for coordinated, rights-based alternatives that move beyond consensus politics and toward binding commitments. This is essential for transforming political openings into real accountability—and for building a more ambitious future for financing development beyond Seville.

What a rights-based approach to development financing can offer

Ahead of FfD4, CESR and our partners proposed a concrete agenda for rights-based financing grounded in binding legal obligations under international human rights law. A Rights-Based Economy reframes financing not as a matter of charity or discretion, but of duty. It means governments must mobilize and spend public resources in ways that guarantee rights, reduce inequality, and repair historic harm.

A rights-based approach includes:

-

Progressive taxation that redistributes wealth and power.

-

Universal, gender-responsive public services funded through grants, not loans.

-

Human rights–aligned debt governance, including a UN-led mechanism for debt restructuring and cancellation.

-

The protection of fiscal space, policy sovereignty, and the right to challenge illegitimate debt.

-

Climate finance based on public resources and historical responsibility—not debt-based instruments.

Together with our allies at the Civil Society Financing for Development Mechanism, we are also calling on governments and international institutions to:

-

Conduct a UN-led review of multilateral development banks and international financial institutions, embedding human rights impact assessments and dismantling entrenched power asymmetries.

-

Conclude a binding convention on international development cooperation, reframing ODA as a legal obligation to address historic and ongoing injustices.

-

Establish a statutory UN debt workout mechanism, including automatic cancellation of unsustainable debt and built-in protections for the rights of women and marginalized communities.

-

Reject the private-finance-first model and ring fence essential services, using gender--responsive and inclusive data to ensure that public finance supports equity, dignity and care.

Gender justice is a non-negotiable pillar of this approach. A rights-based model requires investment in care systems, recognition of unpaid labor, and the full realization of sexual and reproductive rights; none of which can be achieved through financial engineering.

Coalitions of the willing: how we push forward

In the absence of international consensus or strong majorities, a coalition of the willing is needed to push forward concrete, rights-based structural solutions. One of the clearest lessons from PrepCom IV is that the multilateral landscape is shifting: global consensus is no longer a requirement for meaningful progress. In the face of political gridlock, determined alliances are already demonstrating what is possible. This includes unlocking public resources, upholding States’ human rights obligations, and confronting today’s interlocking crises such as unsustainable debt, accelerating climate change, and deepening inequality. Countries have already committed to this path by ratifying binding human rights treaties. Now they must fulfill those obligations.

Across regions and issues, as we have learned from rounds of negotiations that preceded the adoption of the Compromiso de Sevilla, governments are stepping up. Countries including Spain, Mexico, Egypt, Tunisia, Malaysia, Brazil, and Pakistan are leading or supporting targeted alliances focused on advancing gender-responsive budgeting and investment in the care economy, defending progress toward a United Nations Tax Convention, building momentum for a UN convention on Sovereign Debt, and driving systemic reform of multilateral development banks and financial institutions.

These efforts reflect a broader shift in political will and a growing demand for concrete, rights-based alternatives to the current financial architecture. They also show that coalitions built on shared values and a commitment to justice (not merely geographic or economic alignment) can move the agenda forward when formal negotiations stall. These alliances are a vital strategy for keeping ambition alive, building practical momentum, and demonstrating that another path is possible.

Many of these efforts are now being channeled through through the Seville Platform for Action, where over 240 proposals (from governments and civil society) are being submitted alongside the Compromiso de Sevilla to help bridge the gap between negotiated text and real-world change. The Platform is a key opportunity to complement and amplify the outcome text—demonstrating what action looks like beyond negotiated language. Partners and allies, like Jubilee USA highlight that “the text is only one part of the package”: The Platform brings forward these coalition-driven initiatives and must be leveraged to translate political openings into tangible, rights-based commitments.

Civil society has a critical role to play. By connecting national initiatives, amplifying demands, and offering coordinated advocacy grounded in international law, civil society actors help sustain and scale the work of these coalitions. Others (including States, institutions, and movements) should take note. Now is the time to replicate, reinforce, and join these efforts.

As Dr. María Ron Balsera, our Executive Director, put it:

“This is the moment to reclaim multilateralism for people and the planet, not as an empty shell. Let us ensure FfD4 lays the foundation for a just, inclusive, and rights-based global economy: one that renews trust, delivers fairness, and secures a sustainable future for all. The future depends on it.”

Seville must be more than a technical milestone. It must mark a decisive step toward reorienting global economic governance around human rights, climate justice, and decolonial solidarity.