As the First Session of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee to draft the UN Tax Convention begins, advance submissions from states and stakeholders reveal sharp divides between Global South and OECD countries over taxing rights and governance. At the same time, civil society is pushing to anchor human rights, progressivity, and climate justice at the heart of the negotiations. Here, we unpack these early positions and what they could mean for the road ahead.

By Nina Opacic, CESR Fellow and María Emilia Mamberti, CESR's Research and Policy Lead

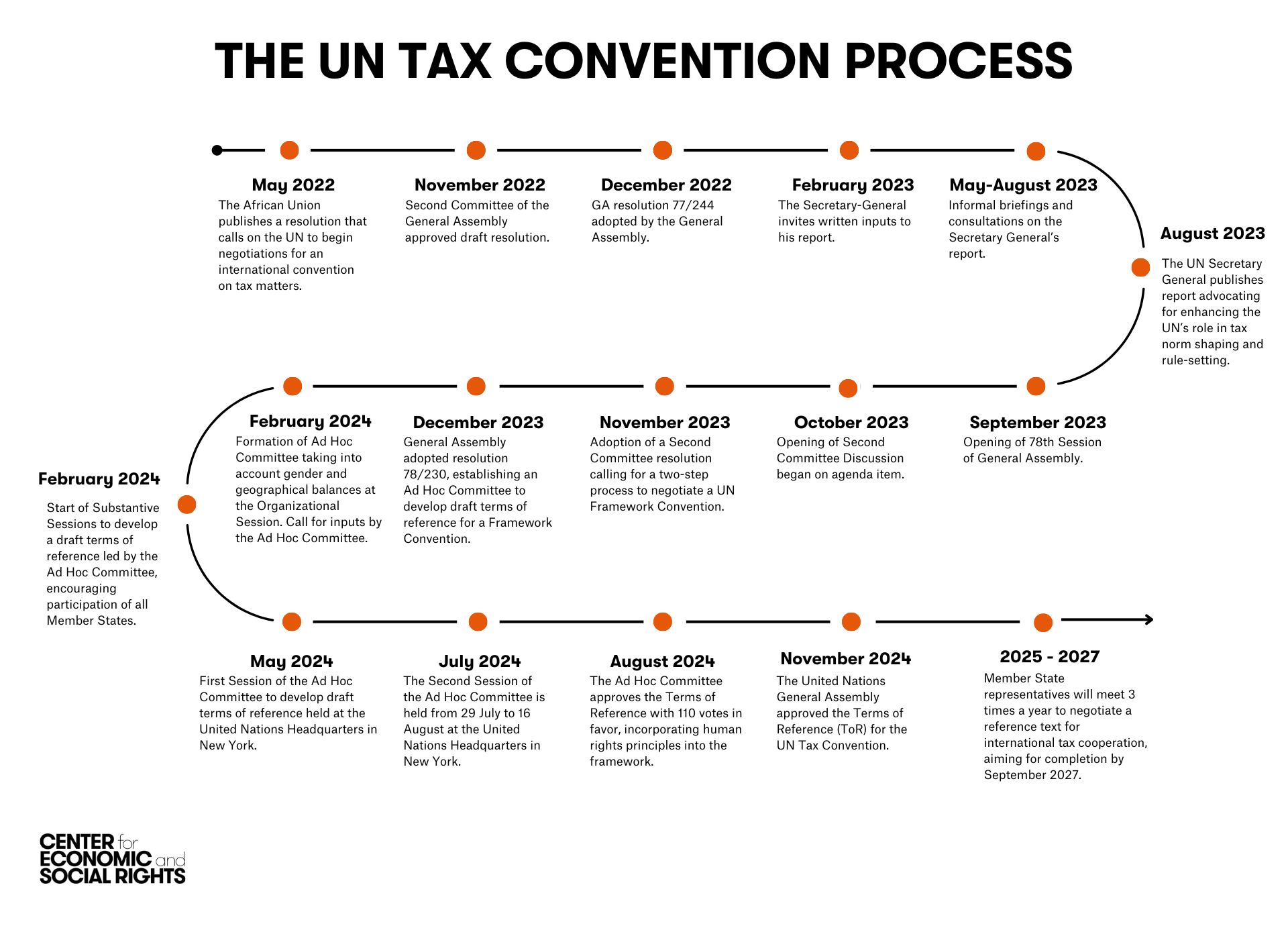

As the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC) starts its first substantive session of negotiations on the UN Framework Convention on International Tax Cooperation (UNTC), momentum is building behind calls for a more inclusive and equitable global tax system (see our analysis of what the Convention can and must address). With the Terms of Reference (ToR) for the Convention adopted earlier this year, delegates are now tasked with developing through three parallel workstreams the Framework Convention’s text (Workstream I) and two early protocols (on the taxation of cross-border services, Workstream II, and dispute prevention and resolution, Workstream III).

Ahead of the session, stakeholders including Member States, intergovernmental organizations, civil society, and the private sector, submitted written inputs responding to draft issues notes developed by each workstream. These inputs offer a first glimpse into the shape of the negotiations and the tensions likely to define them.

Here, we analyze those inputs, focusing on Workstream I, which centers on the Convention’s substantive commitments and received a total of 57 submissions— including 29 from Member States and regional groups, 6 from international organizations, 20 from civil society and academia, and 2 from business. Of the Member State submissions, 11 came from European countries, 6 from the Asia-Pacific region, 5 from Latin America and the Caribbean, 4 from Africa, and 3 from the Middle East or other regions. Notably, while several European countries submitted individually, the African Union was the only regional bloc to present a unified position.

Explore the key milestones of the UN Tax Convention process and learn why they matter for human rights and economic justice. Read more in our FAQs.

Scope of commitments

There is broad agreement across submissions that the Convention’s commitments should be framed in broad and flexible terms. While Global South governments such as Brazil, Ghana, Nigeria, and Indonesia emphasized flexibility to accommodate national contexts and evolving realities, several OECD countries supported high-level commitments to maintain feasibility and avoid legal or procedural overload at this stage. Some countries such as the UK and Czechia think that it is more productive to begin with overarching principles and objectives, as commitments would then flow from them.

Differences emerge in terms of what should be included within the commitments. The Africa Group argued that the commitments should not be limited to the list in paragraph 10 of the ToR, which includes issues such as fair allocation of taxing rights, tax evasion and dispute resolution. Proposals included adding the taxation of income from natural resource extraction. Some OECD countries cautioned against expanding the scope too far, expressing concern that it could overburden negotiations or blur the distinction between the Convention and its Protocols. Austria explicitly stated that it is not reasonable to consider additional elements beyond the TOR.

Avoiding Duplication with the OECD

A key division emerges from the question of how the Convention should relate to existing frameworks. Several countries, such as Austria, Belgium, Czechia, Ireland, and Switzerland, argued that the UN process should complement rather than duplicate the work of the OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework and other international fora. They emphasised risks of fragmentation, double-taxation, over-taxation and hindrance of cross-border trade and investment.

Czechia and France and other OECD countries also emphasised these factors in relation to dispute resolution – noting that any dispute resolution mechanism must remain distinct and not overlap with, or deviate from existing standards in the UN and OECD Model Tax Conventions.

Closely tied to this is a growing rhetorical shift in how some countries choose to describe the current international tax system. Countries such as Ireland, Sweden, and the Republic of Korea urged negotiators to adopt more neutral or “constructive” language, pushing back against references to the system as "unfair." Given that the UN Secretary-General’s 2023 report launching this process explicitly documented the structural unfairness of the current system, particularly for developing countries, this shift reflects a notable reframing and arguably undermines the good faith basis on which the Convention was initiated. For other countries, including Brazil, Colombia, and the Africa Group, the purpose of the Convention is precisely to redress these long-standing inequities and move away from a system shaped disproportionately by OECD countries and their interests.

Allocation of taxing rights

While nearly all submissions recognized the need for fairer allocation of taxing rights and the limitations of the current rules in capturing value from modern – especially digital – business models, the definition of “fairness” remained contested. Several European States cautioned that “fairness” is too subjective to serve as a basis for legal commitments and called for a stronger grounding in economic efficiency, tax neutrality, and legal certainty. Switzerland proposed reaching a common understanding of fairness to avoid ambiguity, while the Africa Group argued that fairness should intentionally remain undefined at the level of commitments, allowing room for evolving interpretation and contextual application. The Republic of Korea also raised concerns about the use of “value creation” as a guiding concept, citing its vagueness and potential for divergent interpretations. Yet, human rights law and CESR’s analysis show that fairness in taxation can be made operational in practice, for example by ensuring adequate revenue mobilization, limiting regressive tax measures, and embedding progressivity and equity as guiding principles (see our technical note on aligning tax cooperation with human rights in the UN Tax Convention).

Several Global South countries, including Indonesia, Colombia, and Morocco, explicitly supported a shift toward source-based taxation. These submissions advocated for new nexus concepts, such as significant economic presence, which would allow countries to tax income derived from economic activity within their jurisdiction, even in the absence of physical presence. Indonesia agreed that taxing rights should be based on real economic contribution, while Colombia and others framed this as a question of fairness and development rights. In contrast, countries like France and Singapore expressed strong reservations about moving away from existing principles like physical presence or the arm’s length principle. France specifically defended the OECD Model Convention’s Article 7, which governs business profits and requires a permanent establishment in order for a country to tax foreign businesses, which France argued produces appropriate outcomes and ensures legal predictability. France also rejected the generalization of gross-basis taxation and new nexus rules, cautioning that it could lead to double taxation and economic inefficiencies.

In sum, while there is broad recognition of the need to modernize the allocation of taxing rights, deep disagreements remain between Global South and Global North countries over how to frame key principles such as fairness, economic activity, and value creation, and whether the Convention should codify or leave them open for interpretation in subsequent protocols.

Sustainable Development

Most Member States welcomed the inclusion of a commitment linking international tax cooperation to sustainable development. Brazil went the furthest, encouraging a move beyond pure declaratory language by embedding normative and operational principles such as equitable allocation of taxing rights, tax progressivity, domestic resource mobilization, inclusive governance, and safeguards against harmful tax practices. Germany emphasised that the Compromiso de Sevilla, the outcome document from the Fourth International Conference on Financing for Development (Ffd4), provides a solid basis for designing further commitments including on progressive taxation, inequalities, effective taxation of High-Net-Worth Individuals (HNWIs), environment, gender and Human rights, while France proposed operationalizing this language through concrete tools like green budgeting and environmental levies.

Other submissions, including from Spain and the Netherlands, warned against expanding the scope too far beyond core tax issues. Czechia, Spain and the Republic of Korea noted that current description is insufficient and needs to be clarified.

Ramy Mohamed Youssef, chair of the INC, opens the session on August 4, 2025.

Governance and decision-making

A final point of tension is how decisions under the Convention will be made. Austria explicitly emphasized the importance of consensus-based decision-making to ensure broad participation, a view echoed more implicitly by countries such as Ireland and Switzerland. Business stakeholders such as KPMG and the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) also strongly supported a consensus-first approach, warning that majoritarian outcomes could undermine legitimacy or lead to disengagement (see below for our analysis of other stakeholders’ submissions). Others, particularly from the Global South, warned that requiring consensus risks entrenching the status quo and undermining the Convention’s legitimacy.

Several submissions, mainly from the Global South, also urged that structural and governance provisions, including the role and composition of the Conference of Parties, Secretariat and Subsidiary Bodies, be prioritized early in the negotiation process, stressing the importance of fair procedures to achieve inclusive and effective tax cooperation.

Civil Society and other stakeholders: advancing rights-based agendas

Human rights were invoked directly or indirectly in 90% of civil society submissions. CESR and allies have previously highlighted the importance of embedding human rights in the Convention’s foundations, including during the ToR negotiations. Organizations including CESR and the Global Alliance on Tax Justice (with over 100 signatories), emphasized the role of tax cooperation in fulfilling states’ human rights obligations, particularly in mobilizing resources to reduce inequalities, finance social protection, and support climate and gender justice. They argued that fairness should not be treated as a purely subjective notion but grounded in international norms of equity, progressivity, and redistributive justice. CESR noted that some human rights treaty bodies have already used the term “fair” in their monitoring work of member states’ policies, providing interpretative guidance on the scope of fair taxation. For example, the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights has found tax systems to be unfair when revenues are too low, when exemptions and weak anti-fraud measures undermine resource mobilization, when indirect taxes are overly relied on, or when tax policies fail to curb rising inequality.

Promoting equality and progressivity

Many civil society submissions positioned progressive taxation as central to achieving substantive equality within and between countries. Organizations such as the Independent Commission for the Reform of International Corporate Taxation (ICRICT), Oxfam, the Global Alliance for Tax Justice (GATJ), and CESR called for the Convention to explicitly recognize the redistributive function of tax systems, and to embed commitments to tax progressivity, particularly through the effective taxation of High-Net-Worth Individuals and multinational corporations. Several submissions supported the creation of new global standards to ensure HNWIs pay their fair share, noting that under current arrangements, the ultra-rich often face lower effective tax rates than ordinary citizens. Proposals included globally coordinated wealth taxes, increased transparency around offshore assets, and minimum effective taxation thresholds. These calls were frequently linked to the Compromiso de Sevilla, which commits states to align their fiscal systems with the goals of reducing inequality, promoting shared prosperity, and financing universal public services. Civil society groups urged that the Convention reflect this vision, and that equality and progressivity be treated as binding principles rather than aspirational values.

Linking tax to climate and gender justice

Numerous submissions highlighted the importance of tax justice for advancing gender and climate equity. Organizations including the Forest & Finance Coalition, and the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) and Public Services International (PSI) called for a sub-commitment on progressive environmental taxation, aligned with the polluter-pays principle, to support climate finance and just transitions. Several submissions proposed concrete tools, such as earmarking a share of digital services taxes for education, climate, or care systems.

Gender-responsive taxation was a recurring demand from CSOs. Some proposed integrating gender impact assessments into tax policy and designing tax rules to reduce gendered inequalities in access to public goods..

Transparency

Transparency also emerged as a priority. Numerous groups, including the Financial Transparency Coalition (FTC), Greenpeace, and Tax Justice Network (TJN) called for commitments to the “ABCs of tax transparency” – automatic exchange of information, beneficial ownership registries and country-by-country reporting (public and disaggregated). Many submissions stressed the need for common but differentiated responsibilities, urging that developing countries receive tax information on a non-reciprocal basis, at least initially, and be granted technical and institutional support to implement transparency mechanisms effectively.

Contributions on other substantive issues of the Convention

Importantly, civil society actors offered concrete proposals on the allocation of taxing rights. A large number of submissions called for a shift toward unitary taxation with formulary apportionment, supplemented by an ambitious minimum effective corporate tax rate. In line with the position of countries in the Global South, they stressed that taxing rights should be allocated based on real economic activity, such as employment, sales, and assets, and not easily manipulated indicators like contractual allocation of profits or location of intangibles.

Many submissions also warned that without coherence between the Convention and other international frameworks, including the Compromiso de Sevilla (where states have pledged to promote tax progressivity, strengthen the voice of developing countries in the international tax architecture, and to enhance tax transparency, including beneficial ownership transparency), the UNFCCC ( including the commitment to make finance flows consistent with low greenhouse gas emissions and climate-resilient development), and existing human rights treaties, the Convention risks being disconnected from broader development and climate justice agendas. These actors called for cross-referencing existing UN frameworks and embedding the Convention within a broader rights-based multilateral landscape.

Participation and governance

A number of submissions raised concerns about the limited access civil society has had to INC sessions to date, particularly in online and informal formats. Many called for clearer rules around observer participation and the institutionalization of meaningful, timely, and informed civil society engagement throughout the negotiation and implementation processes.

There was wide consensus among non-state actors that the Convention must not be limited to commitments, and that priority should also be given to other Convention elements during initial negotiations. Submissions stressed the importance of establishing a robust institutional architecture, particularly a Conference of Parties with decision-making power, a permanent Secretariat, and effective review mechanisms. Many urged that the governance provisions in paragraph 13 of the ToR be given equal weight alongside substantive commitments.

Early protocols

While this blog focuses on Workstream I, which is responsible for developing the overarching framework of the Convention on which the protocols will ultimately be based, it is worth noting the emerging dynamics in the other two workstreams. In Workstream II, which addresses the taxation of cross-border services, discussions reveal significant tensions over whether new rules should prioritize net-basis taxation (typically seen by Global North countries as more “economically precise”) or gross-based withholding taxes, which are often simpler to administer and preferred by many developing countries. The debate also touches on how to interpret value creation and whether the Convention should depart from or align with existing international frameworks, particularly the OECD Model Convention. Meanwhile, Workstream III, focused on dispute prevention and resolution, surfaces sharp divides around multilateral cooperation versus arbitration-based mechanisms. After their experience with arbitration in other areas, many Global South actors caution against binding arbitration and emphasize state-to-state dispute resolution with strong safeguards for transparency, fairness, and accessibility.

The first round of submissions under Workstream I reveals both political divides and potential areas of convergence. While Global South countries and civil society actors push for a transformative, inclusive, and rights-based Convention, several OECD countries remain cautious, favoring a more incremental approach centered on coherence with existing systems.

Despite this, a common thread runs through many submissions: recognition that the current international tax system is not delivering for all, and that reform must balance national sovereignty with the collective urgency of mobilizing resources for human rights' fulfillment, sustainable development, equity, and climate action. As negotiations advance, CESR will continue tracking and supporting efforts to embed human rights, fairness, and transparency into the foundations of the new tax convention.

For more analysis and updates, see our latest technical note on the UN Tax Convention and follow us on LinkedIn and Bluesky.