As the UN Tax Convention's Terms of Reference (ToR) have been approved, the negotiations revealed a tapestry of complex issues and significant compromises. From the critical inclusion of human rights to the conspicuous absence of explicit environmental and gender considerations, the road to this draft has been anything but straightforward. In this analysis, we dissect the key elements from the recent negotiations, delving deeper into the most pivotal topics and examining their implications and the pathways forward. As CESR continues to engage in this critical process, our focus remains on ensuring that human rights principles and substantive commitments are firmly embedded in the final Convention framework.

By: Charlotte Inge and Matt Forgette, CESR Fellows

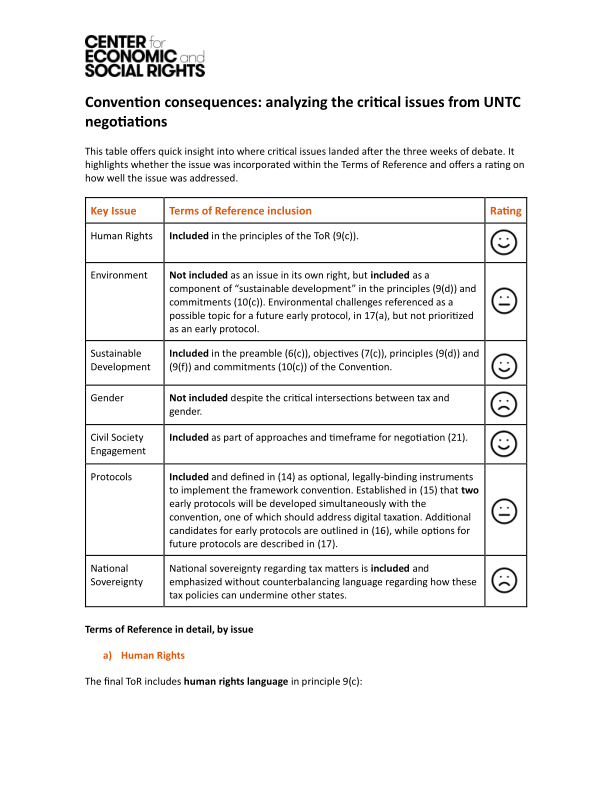

This table offers quick insight into where critical issues landed after the three weeks of debate. It highlights whether the issue was incorporated within the Terms of Reference, and offers a rating on how well it was addressed.

|

Key Issue |

Terms of Reference |

Rating |

|

Human Rights |

Included in the principles of the ToR (9(c)). |

|

|

Environment |

Not included as an issue in its own right, but included as a component of “sustainable development” in the principles (9(d)) and commitments (10(c)). Environmental challenges referenced as a possible topic for a future early protocol, in 17(a), but not prioritized as an early protocol. |

|

|

Sustainable Development |

Included in the preamble (6(c)), objectives (7(c)), principles (9(d)) and (9(f)) and commitments (10(c)) of the Convention. |

|

|

Gender |

Not included despite the critical intersections between tax and gender. |

|

|

Civil Society Engagement |

Included as part of approaches and timeframe for negotiation (21). |

|

|

Protocols |

Included and defined in (14) as optional, legally-binding instruments to implement the framework convention. Established in (15) that two early protocols will be developed simultaneously with the convention, one of which should address digital taxation. Additional candidates for early protocols are outlined in (16), while options for future protocols are described in (17). |

|

|

National Sovereignty |

National sovereignty regarding tax matters is included and emphasized without counterbalancing language regarding how these tax policies can undermine other states. |